Pedagogical Foundations

We call Dialog Pedagogy the pedagogical model that aims at the comprehensive development of students, a model that has been developed at the Alberto Merani Institute over the last two decades.

We understand development as a process mediated by culture and characterized by the transition from simpler to more complex structures. Dialog Pedagogy teaches students to think better, live better, and act better.

In implementing Dialog Pedagogy, we recognize the different human dimensions, the contextual, cultural, historical, social, and mediated nature of development; therefore, we consider the development of comprehensive competencies to be the primary task of the school.

At the methodological level, we believe that development is only possible by acting in an interstructural manner; that is, by simultaneously recognizing the essential and active nature of culture and students.

The former was postulated by sociocultural approaches that adequately understood the individual in their social and historical context and as a representative of culture. While the latter was brilliantly characterized by Piagetian genetic psychology.

Regarding the role of the protagonists of learning, we consider it essential to vindicate the role of the subject in the construction of knowledge and of the student in learning. This implies recognizing the existence of personal elements, nuances, and meanings in all individual representations.

However, the predominance given to personal construction over cultural ones and the undervaluation of the process of cultural mediation led us to distance ourselves from models derived from pedagogical constructivism and to move closer to sociocultural approaches, represented in particular in the theses of Davidov, Leontiev, Vygotsky, Wallon, Bruner, Van Dijk, and Merani.

In this way, we attempt to overcome cognitive biases in education and strive to work toward a model that guarantees the comprehensive education that has been so elusive in educational practice. (Colombia: A Country Without a Compass in Education)

This proposal has been supported by numerous books and articles. Notable among these are: Argumentative Competencies (De Zubiría, 2005), Pedagogical Models (de Zubiría, 2006), Cycles in Education (De Zubiría et al., 2010), How to Design a Competency-Based Curriculum (De Zubiría, 2013), and Education Under the Microscope (De Zubiría et al., 2015).

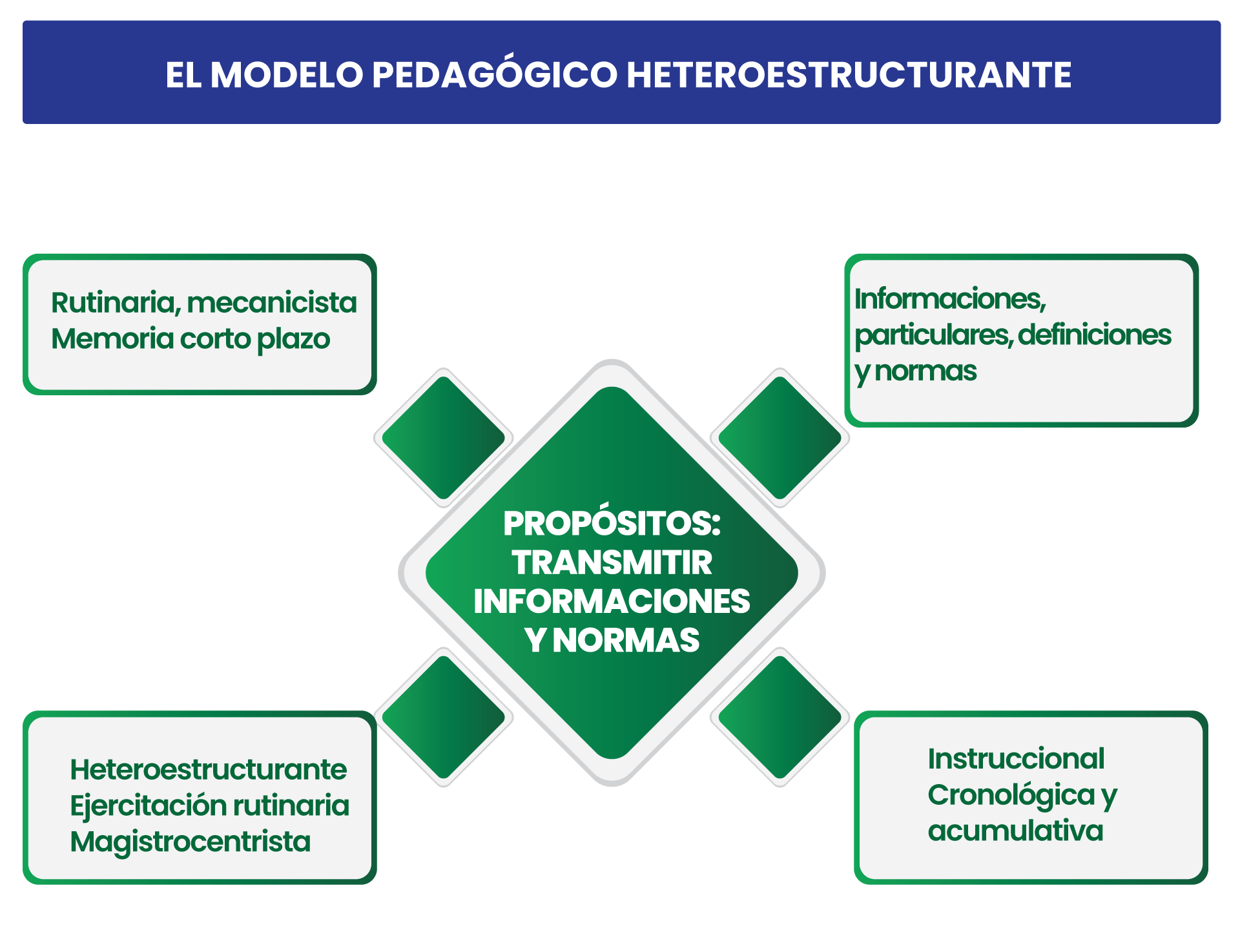

In contrast to the widely dominant and widespread heterostructuring approaches worldwide, Leontiev, Vygotsky, Wallon, Bruner, Van Dijk, and self-structuring approaches have emerged since the beginning of the 20th century, attempting to challenge the Traditional School.

At the beginning of the 20th century, they took the form of New and Active Schools, and in the final decades of the same century, they assumed the name "constructivist currents." But in the face of these, a dialogical and interstructuring model will almost certainly have to emerge (Not, 1983), which, while recognizing the active role of the student in learning, recognizes the essential and determining role of mediators in this process; a model that guarantees a dialectical synthesis.

Such a dialectical synthesis would have to recognize in heterostructuring models the fact that, indeed, knowledge is a construction external to the classroom and that, undoubtedly, practice and reiteration play a central role in the learning process, as long as they are always carried out in diverse contexts. These two aspects are often denied by self-structuring models.

However, the necessary current synthesis will have to diverge from the predominant role that these teacher-centered approaches assign to routine and mechanical processes and from the very passive role they assign to the student in the learning process.

Likewise, a dialectical synthesis would have to recognize in the Active School and constructivist approaches the validity of acknowledging the active role that the student plays in every learning process and the purpose of understanding and intellectual development that they assign to the school; but it must distance itself from the significant undervaluation that these approaches place on the function and role of mediators in every learning process, and from the diminished importance in which they continue to place the practical and affective dimensions of education.

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration

In short, it must be recognized that knowledge is constructed outside of school, but that it is actively and inter-structuredly reconstructed through pedagogical dialogue between the student, knowledge, and the teacher. For this to happen, it is essential to have the appropriate mediation of a teacher who intentionally and transcendently fosters the student's comprehensive development. This approach concludes that the purpose of education cannot be centered on learning, as schools have believed for centuries, but rather on development.

Today, a dialogical pedagogical model must recognize the diverse human dimensions and the obligation that schools and teachers have to develop each of them.

As educators, we are jointly responsible for the cognitive dimension of our students; but we also have equal responsibilities in developing an ethical individual who is outraged by abuses, becomes socially sensitive, and feels responsible for his or her individual and social life project. It is not simply a matter of transmitting knowledge, as the Traditional School mistakenly assumed, but rather of developing more intelligent individuals at the cognitive, affective, social, and practical levels. And this development relates to the diverse human dimensions.

The first dimension is linked to thought and language; the second to affect, sociability, and feelings; and the last to praxis and action, based on the "subject who feels, acts, interacts, and thinks," as Wallon (1987) said.

Get the texts on Dialoguing Pedagogy here: Magisterio - Julián De Zubiría »

Español

Español